Bouba and Kiki: When Flavour, Words, and Shapes Collide

Have you ever described a whisky as being rounded?

Or a wine as being sharp?

If so, you are not alone. However, it’s something that fascinates me as I ponder the complexities of flavour from my secret underwater headquarters. Such associations even venture beyond flavour as we consider how personality traits can swing between being a well-rounded individual and being a bit edgy. But as it turns out there’s science behind this stuff, and the implications go deeper than a nuclear submarine.

Let’s Talk About Sound Symbolism

This isn’t poetic license, scientists have found that sweet, mild flavours really are often associated with round, smooth shapes and sounds, while sharp, bitter or tangy tastes tie to jagged lines and edgy sounds. Not only that, even ChatGPT is in on the act too by making the same associations [1]. In short, our taste receptors, eyes, ears, and nose gossip with each other as we sniff, sip, and savour.

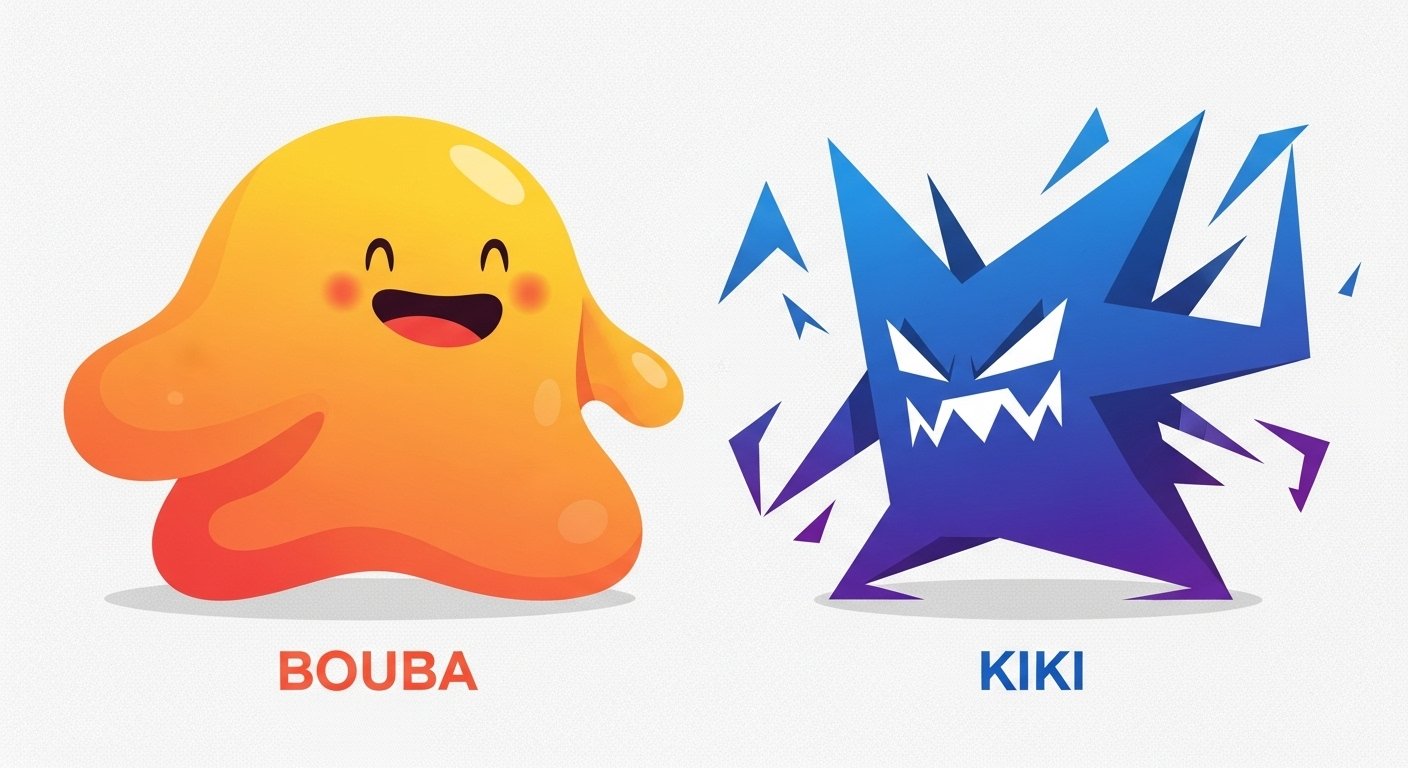

You may have heard of the bouba–kiki effect. It revolves around the fact that people across different cultures and languages consistently match nonsensical words like ‘bouba’ to round, blobby shapes and ‘kiki’ to spiky, star-like shapes [2]. This was first demonstrated by the Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Köhler in 1929 (his original version used baluba and takete).

Köhler’s experiment is the foundational demonstration of sound symbolism, showing that the relationship between sounds and meaning is not entirely arbitrary. While working on the island of Tenerife, Köhler showed participants two abstract shapes - one rounded and blob-like and one angular and spiky. He then asked them which shape should be called ‘baluba’ and which ‘takete’.

Emotional Code Shapes Perception

The Bouba–Kiki effect may sound like a curious quirk of perception. But the findings are striking because they appear to cut across language, culture, and age. It suggests that sounds and shapes are not perceived in isolation, but are linked by something deeper. Something that also reaches into the realms of flavour.

When people are asked to match shapes to tastes, the results mirror Bouba–Kiki almost perfectly. Rounded shapes are more likely to be judged as sweet and pleasant, while angular shapes are more likely to be judged as sour and unpleasant. Crucially, this mapping does not depend on tasting anything at all. Participants are responding to abstract shapes and abstract words, yet their judgments are highly consistent.

Several explanations have been proposed for the Bouba–Kiki effect. Some researchers emphasise statistical learning, arguing that sound–shape correspondences emerge from regularities in language and environment. Others point to embodied articulation, noting that the mouth movements used to produce sounds like kiki are sharper and more constrained than those used for bouba. Still others frame the effect in terms of sensorimotor contingencies linking perception and action.

While these accounts differ in emphasis, they converge on a common outcome: certain sounds and shapes reliably feel more pleasant, safer, or more aversive than others. For the purposes of flavour perception and design, affective valence offers the most parsimonious explanation, because it integrates across sensory modalities and predicts why similar correspondences appear even when no learning, articulation, or action is involved.

The Beauty of Symmetry

Symmetrical shapes with fewer elements are more likely to be judged as pleasant and sweet, while asymmetrical, complex shapes are more likely to be judged as unpleasant and sour [3]. In some cases, these features influence judgments more strongly than curvature itself. This shows that Bouba–Kiki works not because the brain has a special rule about curves and consonants, but because multiple perceptual cues combine to signal emotional value.

Seen this way, Bouba–Kiki is not really about language at all. The sounds bouba and kiki are emotionally different. One is smooth, voiced, and continuous; the other is abrupt, voiceless, and discontinuous. Those acoustic properties carry affective weight. The shapes do the same. The brain aligns them because they feel similar, not because they share any physical resemblance.

This also explains why such effects are robust yet flexible. Cultural differences can shift which visual features dominate, without breaking the correspondence entirely. The underlying mechanism is not a fixed association between a sound and a shape, but a more general tendency to align stimuli that share emotional meaning.

Shapes Define Flavour

In this light, Bouba–Kiki becomes less mysterious and more revealing. It exposes a fundamental principle of perception: sensory inputs are organised by the brain according to affective structure, not sensory modality. Shapes, sounds, and tastes are grouped together not because they are objectively similar, but because they evoke similar internal responses.

And that has broader implications. If something as abstract as a nonsense word can impact how we perceive a shape, then flavour, branding, and experience design are never just about molecules, visuals, or sounds in isolation. They are about how the brain weaves those inputs into a coherent emotional experience. One that feels intuitive, natural, and self-evident, even though it exists only in perception.

These flavour–shape correspondences play out in everyday experiences. Research has demonstrated how cola in a traditional curved soda glass tastes sweeter and more intense than from a straight plastic bottle [4]. Even an Australian craft beer served in a rounded glass was rated fruitier than the same beer in a straight-sided pint4. However, we couldn’t discuss how shape impacts flavour perception without stopping off at the history vault of chocolate.

This is Cultural Vandalism

Image courtesy of Spence [5]

In 2013 something extraordinary happened. Cadbury changed the shape of the chunks in their highly worshipped Dairy Milk chocolate bar from square to rounded [5]. Although not revolutionary, it’s what happened next that was remarkable. An uprising of waggly fingers and shaking fists ensued from die-hard Dairy Milk fans. Why?

Because it tasted sweeter. Too sweet in fact. But Cadbury hadn’t performed any form of recipe wrangling whatsoever. On the contrary. It was purely a cost-saving exercise in the form of shaving a few grams off a bar here and there. The revolt grew with such fury that chocolate champions from up and down the country started an online petition and unleashed their full wrath through the ferocious typing of keyboards.

“This is cultural vandalism.”

“The chocolate is crumblier, less smooth, less creamy and the new shape is just plain wrong.”

“They just don't understand the English culture!”

Conversely, chefs and designers can exploit the effect: make the dishware as curvy as possible, and your dessert will literally taste sweeter to guests. In one example, participants rated vanilla ice cream as more satisfying when the serving bowl had a flared, round edge than when it was sharp-edged, presumably because the smooth rim suggested a softer (sweeter) experienc4. But, perhaps the more important concept to consider is processing fluency.

Flavour Fluency

Processing fluency is a neurodesign principle that describes how easily the brain can interpret and organise a stimulus. When something is processed fluently, neural activity is faster, smoother, and more predictable because the stimulus aligns well with prior expectations and perceptual templates. In simple terms, like a long-haul EV driver, the brain is chiefly concerned with conserving energy. And it does this by making a few assumptions based on past experiences.

This ease or difficulty is not experienced as effort in the sense of going to the gym. When something is easy to perceive or understand, the brain experiences that ease internally, but it does not recognise it as a property of its own processing. Instead, it projects that feeling outward and treats it as a quality of the object. Low effort stimuli are therefore judged as more pleasant, safer, higher quality, or more trustworthy, while high effort stimuli often feel tense, unpleasant, or aversive.

Neurodesign applies this principle across sensory domains. Visual forms, sounds, words, and even flavours that are coherent and predictable are experienced more positively because they are processed efficiently. The goal is not to eliminate complexity, but to manage it so that stimulation remains engaging without overwhelming the system. Effective design operates within this optimal fluency zone, shaping perception in ways that feel intuitive rather than consciously persuasive.

Why Bouba and Kiki Matter

All of this isn’t just academic trivia. For anyone in the flavour industries, hospitality design, or visitor centre experiences, it highlights hidden variables that can either make or break an experience. Whether it’s the shape of your wine goblets, the weight of your whisky glasses, or the feel of your cutlery. We can also consider branding psychology through bottle design, packaging colour, and even the subtle lines in your logo. When it comes to flavour, everything matters.

By exploring these principles in practice, you can see how they shape real-world experiences. Our workshops and training sessions are designed to bring these ideas to life, giving you hands-on insight into how perception shapes flavour and design, so you can apply them with confidence in your own work. If you want to gain deeper insights into how you can leverage psychological insights to guide your guests experience, click on the button below.

Key Takeaways

People consistently describe flavours using shape-based language (rounded, sharp) because taste, sound, shape, and emotion are cognitively linked, not metaphorically but perceptually.

The Bouba–Kiki effect shows that humans reliably map sounds, shapes, and tastes together across cultures, revealing that perception is organised by shared emotional meaning rather than by individual senses.

Rounded, smooth, and symmetrical shapes tend to feel sweeter and more pleasant, while angular, complex, and asymmetrical shapes feel sharper, sourer, or more unpleasant — even without tasting anything.

These correspondences arise from affective valence and processing fluency: stimuli that are easier for the brain to process are experienced as more pleasant and higher quality.

Changes in physical form alone, such as glassware or food shape, can measurably alter flavour perception without altering the recipe, as seen in drinks, beer, ice cream, and chocolate.

Design elements work by aligning multiple sensory cues into a coherent emotional signal; when they clash, people often report discomfort or ‘something being wrong’ with the product.

For flavour, hospitality, and brand design, perception is never just about ingredients: shapes, sounds, materials, and visuals all shape how flavour is experienced and remembered.

References

1. Motoki, K., Spence, C., & Velasco, C. (2024). Colour/shape-taste correspondences across three languages in ChatGPT. Cognition

2. Ćwiek, A., Fuchs, S., Draxler, C., Asu, E. L., Dediu, D., Hiovain, K., Kawahara, S., … Winter, B. (2021). The bouba/kiki effect is robust across cultures and writing systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences

3. Velasco, C., Salgado‐Molina, M. M., Marmolejo‐Ruiz, P. A., & Spence, C. (2015). On the importance of sensory expectations: The influence of subtle and explicit expectations on sweetness perception in the real world. Frontiers in Psychology

4. Spence, C., & Van Doorn, G. (2017). Does the shape of the drinking receptacle influence taste/flavour perception? A review. Beverages

5. Spence, C. (2013). Unraveling the mystery of the rounder, sweeter chocolate bar. Flavour